Grammarly’s Gibberish

The Gibberish

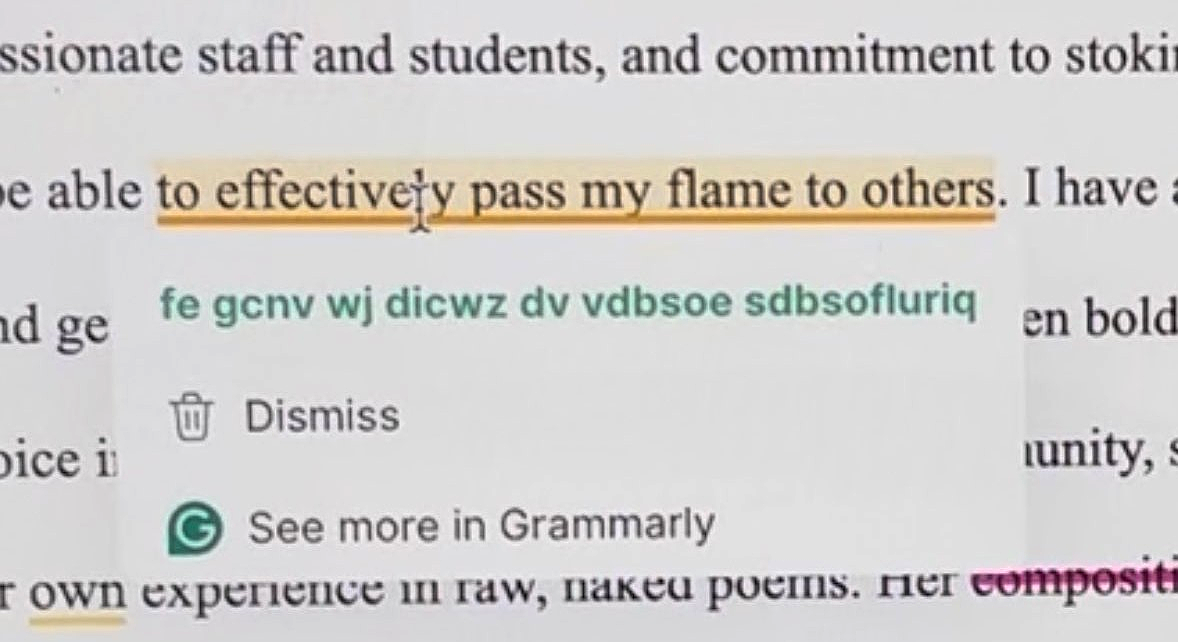

A tweet was making the rounds today that showed this bizarre Grammarly suggestion:

At first, the suggestion looks like a garden-variety AI hallucination. The kind we love to screenshot and dunk on. But if you stare at it for half a second longer, something is off in a very specific way: every word in the gibberish has the same length as some word in the original sentence. The only obvious reordering is that the longest word has been moved to the end.

Original text

Grammarly suggestion

Ignore the word movement for a moment. Word-length by word-length, the gibberish lines up with the English. That strongly suggests the scrambled output isn’t just random nonsense, but is derived from a meaningful suggestion.

Based on my experience with how Grammarly behaves, I have a pretty good guess about what that suggestion was. Grammarly really doesn’t like split infinitives (e.g., “to effectively pass”) and likes to “fix” them (which, from a linguistic perspective, is just arbitrary English-teacher prescriptivism, but I digress). That points to the actual suggestion being:

If you accept that, the next question becomes: what mapping turns this normal English into fe gcnv wj dicwz dv vdbsoe sdbsofluriq?

We know it can’t be a simple monoalphabetic substitution, because the same letter gets turned into different gibberish letters in different places (t becomes both f and d). So if there is a real system here, it has to be doing something position-dependent i.e. the mapping from input to output changes as you move along the string.

A very simple way to get that behavior is to give each character its own little shift instruction. Imagine you write down the alphabet in a circle, and for each letter of the suggestion you secretly decide how many steps to move forward around that circle before you write down the output letter. At position 1 you might move 3 steps, at position 2 you might move 17 steps, and so on. The scrambled text you see is what you get after applying all of those per-character shifts.

That’s basically what a Vigenère-style cipher does. Instead of one fixed substitution for the whole message, you have a key, a sequence of shifts, and each character in the message gets moved along the alphabet according to the corresponding entry in that key [1].

If we assume the clear English suggestion is the plaintext and the gibberish is the ciphertext produced by per-character shifts, then we can work backwards and recover the sequence of shifts, the “key”, that would make the two line up.

In real cryptographic settings you usually don’t know the plaintext in advance, which makes this kind of key recovery hard. Here we have the luxury of knowing both strings, so recovering a candidate key is just arithmetic.

Key Recovery

1. Plaintext ↔︎ Ciphertext

First, let’s be explicit about what we’re calling plaintext and ciphertext.

From the context and word lengths, Grammarly’s intended suggestion is:

We’ll treat that as the plaintext, and the on-screen gibberish as its enciphered form. To line them up for a Vigenère-style analysis, we strip spaces and lowercase everything so that each character has a partner:

Clear : topassmyflametootherseffectively

Cipher: fegcnvwjdicwzdvvdbsoesdbsofluriq2. Map Letters to Numbers

Next, we convert letters to numbers:

A=0,\ B=1,\ C=2,\ \dots,\ Y=24,\ Z=25.

You could just as well start at A=1 (or anything else) and you’d still recover the same key, because any constant offset cancels when you subtract. The only requirement is that you keep the alphabet in a fixed order; if you shuffle the order, the arithmetic stops meaning anything.

For the aligned strings above, the first few characters look like this:

| Plain | P_i | Cipher | C_i |

|---|---|---|---|

| t | 19 | f | 5 |

| o | 14 | e | 4 |

| p | 15 | g | 6 |

| a | 0 | c | 2 |

| … | … | … | … |

3. Compute Shifts

Once we have both strings in numeric form, we compute, for each index i, the key value

k_i = (C_i - P_i)\bmod 26.

The first few rows look like this:

| i | P_i | C_i | k_i = (C_i - P_i)\bmod 26 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 5 | 12 |

| 1 | 14 | 4 | 16 |

| 2 | 15 | 6 | 17 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 18 | 13 | 21 |

| … | … | … | … |

Carrying this all the way through gives the following 32-element sequence:

Given any plaintext–ciphertext pair of equal length, you can always define a sequence of per-character shifts like this. The math guarantees that.

4. Convert Back to Letters

Now we map each k_i back to a letter using the same 0–25 labeling.

The first few shifts look like this:

| Shift | Letter |

|---|---|

| 12 | M |

| 16 | Q |

| 17 | R |

| 2 | C |

| … | … |

Concatenating all 32 shifts gives the key:

MQRCVDKLYXCKVKHHKUOXMOYWOMMDZNXSSo if you take Grammarly’s intended suggestion as plaintext and the scrambled output as ciphertext, you can model their relationship as a per-character additive cipher with the key. Using this key, you can run the process in reverse and regenerate the observed gibberish from the clear text.

The Python code below does exactly that:

import string

PLAINTEXT = "topassmyflametootherseffectively"

CIPHERTEXT = "fegcnvwjdicwzdvvdbsoesdbsofluriq"

ALPHABET = string.ascii_lowercase

LETTER_TO_INDEX = {ch: i for i, ch in enumerate(ALPHABET)}

INDEX_TO_LETTER = {i: ch for i, ch in enumerate(ALPHABET)}

def char_shift(plain_char: str, cipher_char: str) -> int:

"""Return the shift (0–25) that turns plain_char into cipher_char (mod 26)."""

p = LETTER_TO_INDEX[plain_char]

c = LETTER_TO_INDEX[cipher_char]

return (c - p) % 26

def apply_shift(char: str, shift: int) -> str:

"""Shift char forward by `shift` positions in the alphabet (mod 26)."""

p = LETTER_TO_INDEX[char]

return INDEX_TO_LETTER[(p + shift) % 26]

def recover_key(plaintext: str, ciphertext: str) -> str:

"""

Recover the per-character key that maps plaintext -> ciphertext

under a Vigenère-style additive cipher.

"""

if len(plaintext) != len(ciphertext):

raise ValueError("Plaintext and ciphertext must be the same length.")

shifts = [

char_shift(p, c)

for p, c in zip(plaintext, ciphertext)

]

return "".join(INDEX_TO_LETTER[s] for s in shifts)

def encrypt_with_key(plaintext: str, key: str) -> str:

"""Encrypt plaintext using a per-position key (same length, additive mod 26)."""

if len(plaintext) != len(key):

raise ValueError("Plaintext and key must be the same length.")

return "".join(

apply_shift(p, LETTER_TO_INDEX[k])

for p, k in zip(plaintext, key)

)This doesn’t prove that Grammarly literally uses a Vigenère cipher internally. All I’ve really shown is that this weird suggestion isn’t nonsense. Under a simple Vigenère-style model there is a deterministic mapping between the gibberish in the tweet and the intended English suggestion.

In other (more formal) words, there exists a key the same length as the text such that, at each position i, if you shift the plaintext letter forward in the alphabet by the amount specified by the key, you get the gibberish letter, and if you shift backward you recover the English. Whether Grammarly really does this in general is a separate question. All I can say is that this particular screenshot fits that model almost suspiciously well.

Why Would Grammarly Do This?

In the original tweet, the suggestion is not coming from a random web interface. It is a tooltip drawn by the Grammarly Chrome extension on top of Google Docs. That detail matters. Whatever produced the weird string is running inside the browser as part of the extension code, not in a server log or some backend dashboard.

Grammarly’s security documentation says that data in transit is protected with TLS 1.2 and that data at rest in AWS is encrypted using AES-256 server-side encryption with keys managed by AWS KMS [2][3]. TLS is designed to provide privacy and integrity between two communicating applications [4], and AES is a standardized block cipher used to protect electronic data [5]. That already covers the usual worries about someone sniffing your traffic or stealing disks out of a data center. An extra Vigenère-style layer on top of TLS and AES does not really change those threat models. If something like the per-character shifting I modeled exists at all, it makes much more sense as an in-browser obfuscation layer that makes suggestion text harder to scrape or casually inspect on the client side.

Reverse-engineering work on Grammarly-related APIs gives a rough picture of the client–server flow. The extension, or another integration, sends your text to Grammarly over a TLS-protected connection, and the backend responds with structured JSON messages that include things like document metadata, scores, and diagnostics [6]. If we plug the per-character shift model into that picture, one plausible story looks like this.

- The server includes the clear-text suggestion somewhere in the JSON response it sends back over TLS [6].

- Inside the extension, the code generates a per-suggestion key. A natural way to do this in the browser would be to call

crypto.getRandomValues()to obtain cryptographically strong random bytes, then reduce those bytes modulo 26 to get per-character shifts [7].

- Before any suggestion is exposed as ordinary text in the page or extension UI, the extension applies those shifts to the suggestion string and produces the scrambled version.

- A small

decryptAndRender()-style routine immediately reverses the shifts and renders the human-readable suggestion into the tooltip the user actually sees.

All of this would live inside the extension content scripts, which Chrome runs in an isolated world, a private JavaScript environment that is separate from the page scripts and from other extensions’ content scripts [8]. In that isolated world, the internal variables that hold the ciphertext, the key, and the plaintext suggestion are not directly visible to arbitrary page scripts. TLS already protects against network sniffers, and once the final suggestion is written into the DOM as regular text other code can of course read it, but this extra layer still raises the bar for naïve scraping and casual debugging of the extension [9].

If the key really were generated fresh for each suggestion, never reused, and drawn from a truly random source, then in the idealized case where the key is as long as the message and only used once, you would have the classic one-time-pad construction. That scheme is information-theoretically secure, which means that the ciphertext alone does not reveal any information about the plaintext beyond its length [10][11]. In practice, using a cryptographically secure generator such as crypto.getRandomValues() gives you random values that are good enough for any realistic attacker in this setting [7]. Either way, for someone who only sees the scrambled string, the ciphertext by itself reveals essentially nothing about the underlying suggestion, while costing the extension only a handful of additions, modulo operations, and array lookups per character, all done locally in the browser.

Seen in that light, the mechanism is less like heavyweight cryptography aimed at protecting user secrets from highly resourced adversaries and more like a lightweight obfuscation wrapper around Grammarly’s proprietary NLP-generated suggestions. It resembles the Caesar-style transforms that closed-source software often uses to keep in-memory strings from being trivially scraped, only here it is applied per suggestion inside a browser extension and layered on top of the usual browser and transport security [8].

So what looks at first like a glitchy AI hallucination turns out, on closer inspection, to be completely compatible with a simple classical cipher tucked inside a modern browser extension. The gibberish is not nonsense.

Neat.

References

- “Vigenère cipher,” Wikipedia. Accessed June 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vigen%C3%A8re_cipher

- Security at Grammarly. “Data encryption,” Grammarly Trust Center. Accessed June 2025. https://www.grammarly.com/security

- Grammarly Support. “Privacy and security FAQ,” accessed June 2025. https://support.grammarly.com/hc/en-us/articles/20916119474829-Privacy-and-security-FAQ

- “Transport Layer Security,” Wikipedia. Accessed November 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transport_Layer_Security

- NIST. “Advanced Encryption Standard (AES),” FIPS PUB 197, 2001. https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/fips/197/final

- bblanchon. reverse_engineering_grammarly_api (README), GitHub. Accessed June 2025. https://github.com/bblanchon/reverse_engineering_grammarly_api/blob/master/README.md

- Web APIs | MDN. “Crypto.getRandomValues() method,” accessed June 2025. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Crypto/getRandomValues

- Chrome Extensions documentation. “Content scripts (isolated worlds),” accessed June 2025. https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions/develop/concepts/content-scripts

- Chrome Extensions documentation. “Stay secure – Use content scripts carefully,” accessed June 2025. https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions/develop/security-privacy/stay-secure

- “One Time Pad (OTP),” CryptoMuseum. Accessed June 2025. https://www.cryptomuseum.com/crypto/otp/

- “One-time pad,” Wikipedia. Accessed November 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad